Introduction

Much has been said about the Simpson’s paradox, the famous statistic paradox that leads to reversing association when adding or removing a covariate.

My intention in this post is not to explain the paradox, as many have done it already before me, instead I just provide an illustration to set the context, and then I focus on how to forge data that leads to this paradox.

This post is named after a very inspiring article by Jakob Cohen [1], explaining how the null hypothesis significance testing is misunderstood and misused, although it is the bread and butter of tens of thousands of statisticians around the world.

The post is also inspired by David Louapre’s Science Etonnante(in french) excellent blog.

An example of Simpson’s paradox

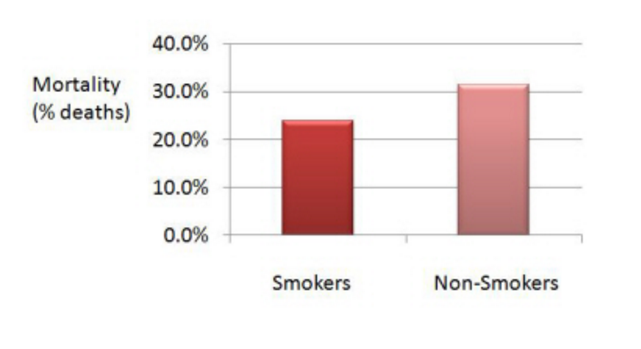

Let’s look at a real study performed in the seventies in a UK village [2]. The researchers surveyed women, smoking and non smoking. They then reported the percentage of women still alive 20 years later.

The result was the following:

The data shows that the mortality was lower amongst the smokers. How surprising! Something must have gone wrong.

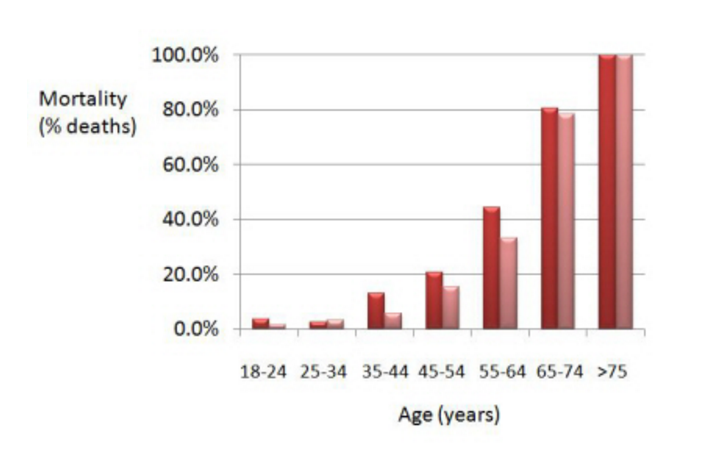

Indeed, if we refine the data and add a covariate, i.e. we now distinguish between classes of age, we see this:

(smokers are in red, non smokers in pink)

What we now observe is that mortality has generally been higher for the smokers than for the non smokers. Sounds more in line we what we expected, doesn’t it?

So what happened? Well, that’s an illustration of the simpson’s paradox. The paradox may happen when an important covariate (factor that has in influence on the result) is missing, and generally under specific circumpstances with unbalanced group sizes (non homogeneity).

There are multiple examples of this paradox appearing in real life situation, including the famous UCI Berkeley students’ admission discrimination case. At first glance, it that appeared the admission ratio for male applicants was higher than that of female applicants (44% versus 35%). However, when splitting data by major, the results no longer showed any discrimination as the admission ratio was approximately similar for both male and females. See this excellent article for more.

The original data

I got interested in forging data whilst studying linear regression. I worked on a small group project and wanted to come up with a striking example, which although it would have coefficients of statistical significance, the regression woud lead to wrong conclusion.

I started with the first study mentionned above (smoking/non smoking). The raw data is presented below

# Initialize environment

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

from __future__ import division

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

%matplotlib inline

# Load the data from the original study

data = pd.read_csv("./smoking.data",delim_whitespace=True)

data

| id | age | smoker | alive | dead | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 18-24 | 1 | 53 | 2 |

| 1 | 2 | 18-24 | 0 | 61 | 1 |

| 2 | 3 | 25-34 | 1 | 121 | 3 |

| 3 | 4 | 25-34 | 0 | 152 | 5 |

| 4 | 5 | 35-44 | 1 | 95 | 14 |

| 5 | 6 | 35-44 | 0 | 114 | 7 |

| 6 | 7 | 45-54 | 1 | 103 | 27 |

| 7 | 8 | 45-54 | 0 | 66 | 12 |

| 8 | 9 | 55-64 | 1 | 64 | 51 |

| 9 | 10 | 55-64 | 0 | 81 | 40 |

| 10 | 11 | 65-74 | 1 | 7 | 29 |

| 11 | 12 | 65-74 | 0 | 28 | 101 |

| 12 | 13 | 75+ | 1 | 0 | 13 |

| 13 | 14 | 75+ | 0 | 0 | 64 |

The data could not be visualised as a scatter plot and neither was it possible to fit a regression line. So I decided to forge it.

Forging a simple example

Let’s “study” the hypothetical effect of smoking on libido.

The idea is to create several separate clouds of points. Each cloud, regressed independantly will have a negative coefficients.

But each cloud is located in such a way that is the regression happens on the whole cloud of points, the regression take place in the other direction

# Forge the data

import random

# Male data cloud

# xm: abscissa data, em = randomness for the ordinate, ym = ordianate, sexm = label

xm = [random.randint(18,35) for _ in range(40)]

em = [np.random.normal(0,7)+5 for _ in range(40)]

ym = [10-.5*xm[i]+em[i] for i in range(40)]

sexm = ["Male" for _ in range(40)]

# Female data cloud

# xf: abscissa data, ef = randomness for the ordinate, yf = ordianate, sexf = label

xf = [random.randint(0,22) for _ in range(40)]

ef = [np.random.normal(0,5) for _ in range(40)]

yf = [-5-.75*xf[i]+ef[i] for i in range(40)]

sexf = ["Female" for _ in range(40)]

# Concatenate the male and female data to be able to display aggregated clouds

xt = xm + xf

yt = ym + yf

sext = sexm + sexf

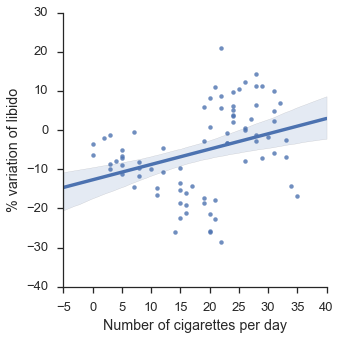

Let’s display the whole data cloud, without differentiating by sex.

import seaborn as sns

x=xt

y=yt

sex=sext

sns.set(style="ticks", context="talk")

data = {"x":xt,"y":yt,"sex":sext}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

g = sns.lmplot(x="x",y="y",data=df)

g.set_axis_labels("Number of cigarettes per day", "% variation of libido")

plt.show()

The line seems to indicate a positive correlation between smoking a libido: the more the smoke, the more libido you have.

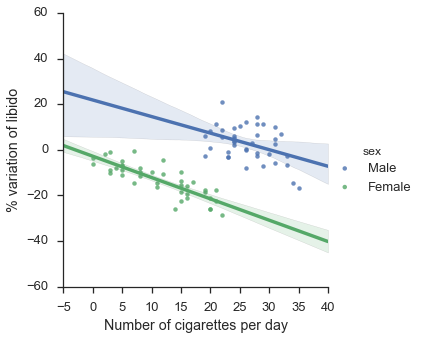

Now let’s add our age covariate.

f = sns.lmplot(x="x",y="y",hue="sex",data=df)

f.set_axis_labels("Number of cigarettes per day", "% variation of libido")

plt.show()

That now looks more as expected… smoking has a negative effect on both groups when taken separately!

Note that in the two graphs, the clouds of points in exactly the same!

Final check… in the first graph, was our coefficient statistically significant?

import statsmodels.api as sm

x_fit = sm.add_constant(x) # Without it intercept is excluded

model = sm.OLS(y, x_fit).fit()

predictions = model.predict(x_fit)

print(model.summary())

OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared: 0.111

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 0.099

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 9.718

Date: Sat, 19 Nov 2016 Prob (F-statistic): 0.00255

Time: 22:41:26 Log-Likelihood: -300.52

No. Observations: 80 AIC: 605.0

Df Residuals: 78 BIC: 609.8

Df Model: 1

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [95.0% Conf. Int.]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const -12.6647 2.636 -4.804 0.000 -17.913 -7.417

x1 0.3917 0.126 3.117 0.003 0.142 0.642

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 2.345 Durbin-Watson: 1.591

Prob(Omnibus): 0.310 Jarque-Bera (JB): 2.253

Skew: -0.340 Prob(JB): 0.324

Kurtosis: 2.538 Cond. No. 47.2

==============================================================================

Warnings:

[1] Standard Errors assume that the covariance matrix of the errors is correctly specified.

x1 coefficient has a p value of 0.003, which is significant if we reject the null hypothesis for p<0.05 !

Forging a multi-class example

This second example uses the same technic as previously, but splits into 3 classes.

# Forge the data

import random

# Age group 15-34

x1 = [random.randint(12,40) for _ in range(40)]

e1 = [np.random.normal(0,6) for _ in range(40)]

y1 = [82-.15*x1[i]+e1[i] for i in range(40)]

age1 = ["15-34" for _ in range(40)]

# Age group 35-54

x2 = [random.randint(5,30) for _ in range(40)]

e2 = [np.random.normal(0,5) for _ in range(40)]

y2 = [75-.3*x2[i]+e2[i] for i in range(40)]

age2 = ["35-54" for _ in range(40)]

# Age group 55+

x3 = [random.randint(0,30) for _ in range(40)]

e3 = [np.random.normal(0,4) for _ in range(40)]

y3 = [68-.45*x3[i]+e3[i] for i in range(40)]

age3 = ["55+" for _ in range(40)]

# Concatenate all the groups data to be able to display aggregated clouds

x4 = x1 + x2 + x3

y4 = y1 + y2 + y3

age4 = age1 + age2 + age3

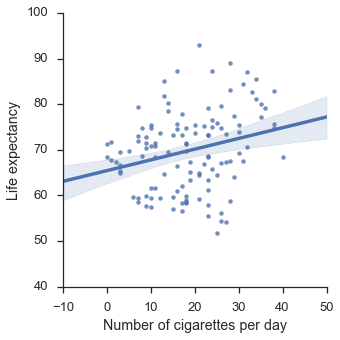

Again, let’s look at the aggregated data (unexepected result), split with covariate (expected result) and the significance factor.

# Display the data without the confounding factor

x=x4

y=y4

age=age4

sns.set(style="ticks", context="talk")

data = {"x":x,"y":y,"age":age}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

g = sns.lmplot(x="x",y="y",data=df)

g.set_axis_labels("Number of cigarettes per day", "Life expectancy")

plt.show()

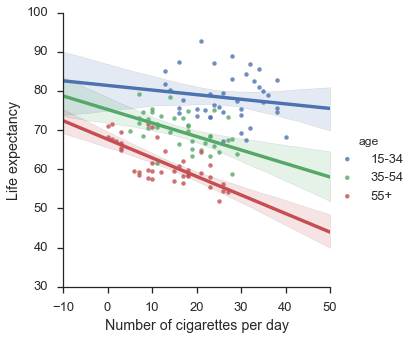

# Show the same data with confounding factor

f = sns.lmplot(x="x",y="y",hue="age",data=df)

f.set_axis_labels("Number of cigarettes per day", "Life expectancy")

plt.show()

# Show the significance of the coefficient

import statsmodels.api as sm

x_fit = sm.add_constant(x) # Without it intercept is excluded

model = sm.OLS(y, x_fit).fit()

predictions = model.predict(x_fit)

print(model.summary())

OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared: 0.067

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 0.059

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 8.491

Date: Sat, 19 Nov 2016 Prob (F-statistic): 0.00427

Time: 22:43:39 Log-Likelihood: -425.24

No. Observations: 120 AIC: 854.5

Df Residuals: 118 BIC: 860.0

Df Model: 1

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [95.0% Conf. Int.]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const 65.4403 1.695 38.598 0.000 62.083 68.798

x1 0.2350 0.081 2.914 0.004 0.075 0.395

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 0.616 Durbin-Watson: 1.230

Prob(Omnibus): 0.735 Jarque-Bera (JB): 0.716

Skew: 0.014 Prob(JB): 0.699

Kurtosis: 2.623 Cond. No. 46.3

==============================================================================

Warnings:

[1] Standard Errors assume that the covariance matrix of the errors is correctly specified.

Generate an example with double paradox

# Forge the data

import random

ar = (8,10)

nr = (10,8)

ap = (15,5)

nP = (17,10)

std = 2

# Male/Smoker

xap = [random.randint(ap[0]-2,ap[0]+2) for _ in range(40)]

e = [np.random.normal(0,1) for _ in range(40)]

yap = [ap[1]+e[i]-1*(xap[i]-np.min(xap)) for i in range(40)]

sap = ["Tobacco" for _ in range(40)]

aap = ["Male" for _ in range(40)]

lap = ["Tobacco + Male" for _ in range(40)]

# Female/Smoker

xnp = [random.randint(nP[0]-2,nP[0]+2) for _ in range(40)]

e = [np.random.normal(0,1) for _ in range(40)]

ynp = [nP[1]+e[i]-1*(xnp[i]-np.min(xnp)) for i in range(40)]

snp = ["Tobacco" for _ in range(40)]

anp = ["Female" for _ in range(40)]

lnp = ["Tobacco + Female" for _ in range(40)]

# Male/E-cigarette

xar = [random.randint(ar[0]-2,ar[0]+2) for _ in range(40)]

e = [np.random.normal(0,1) for _ in range(40)]

yar = [ar[1]+e[i]+.2*(xar[i]-np.min(xar)) for i in range(40)]

sar = ["E cigarettes" for _ in range(40)]

aar = ["Male" for _ in range(40)]

lar = ["E cigarettes + Male" for _ in range(40)]

# Female/E-cigarette

xnr = [random.randint(nr[0]-2,nr[0]+2) for _ in range(40)]

e = [np.random.normal(0,1) for _ in range(40)]

ynr = [nr[1]+e[i]+.2*(xnr[i]-np.min(xnr)) for i in range(40)]

snr = ["E cigarettes" for _ in range(40)]

anr = ["Female" for _ in range(40)]

lnr = ["E cigarettes + Female" for _ in range(40)]

x = xap + xnp + xar + xnr

y = yap + ynp + yar + ynr

s = sap + snp + sar + snr

a = aap + anp + aar + anr

l = lap + lnp + lar + lnr

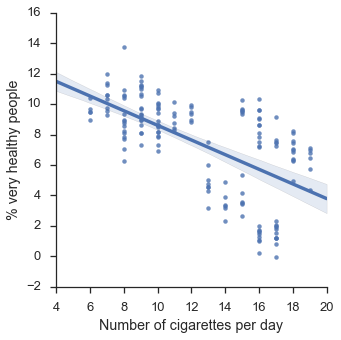

Let’s look at our overall data. Does smoking tobacco or e-cigarettes impact your health?

# Display without confounding factor

data = {"x":x,"y":y,"smoke":s,"athlet":a,"label":l}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

f = sns.lmplot(x="x",y="y",data=df)

f.set_axis_labels("Number of cigarettes per day", "% very healthy people")

plt.show()

Ok, so far so good, it looks like smoking damages your health as expected.

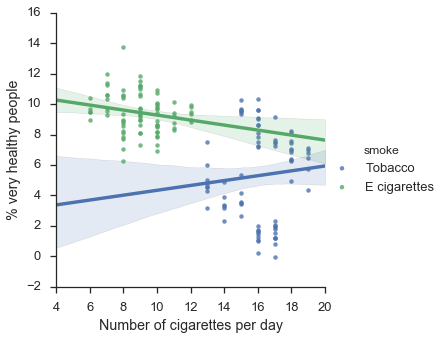

Let’s add a covariate and split by what people smoke.

# Display woth one confounding factor

f = sns.lmplot(x="x",y="y",hue="smoke",data=df)

f.set_axis_labels("Number of cigarettes per day", "% very healthy people")

plt.show()

Uh-oh! Now it appears tobacco is having a positive effect on health, whereas e-cigarettes are slightly harmful. Strange isn’t it?

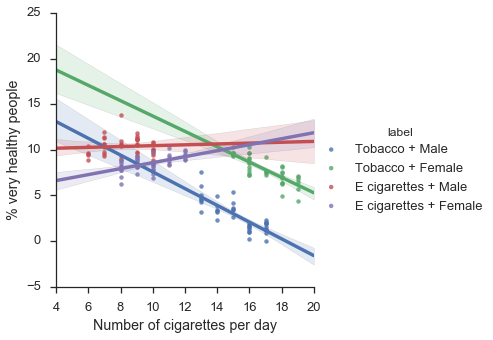

Let’s add again one more covariate!

# Display with two confounding factors

f = sns.lmplot(x="x",y="y",hue="label",data=df)

f.set_axis_labels("Number of cigarettes per day", "% very healthy people")

plt.show()

Now we see a double reversal of the simpson’s paradox! By adding successively new covariates, we were able to obtain successively very different results!

Conclusion

As we just saw, you can get a lot out of data, pretty much you can get them to tell anything you want!

So as a data scientist, you need to be aware of the Simpson’s paradox so you can spot it when it occurs, that’s a no brainer.

But most of all, it shows the importance of being a subject matter expert, or working with one, of area/data you want to process.

References

[1] Cohen. “The earth is round, p<0.05” The American Psychologist 49.12 (1994): 997-1003

[2] Appleton, David R., Joyce M. French, and Mark PJ Vanderpump. “Ignoring a covariate: An example of Simpson’s paradox.” The American Statistician 50.4 (1996): 340-341.