Since I decided to become a data scientist, I have been asked many times what data science is about and what it means to be data scientist.

As often with jobs not well known to the public, it is hard to describe in simple words that people understand and so they can relate the field to some experience or product they are famliar with.

In this post, I will talk about machine learning, the area I personnally find most interesting in data science, and I will then present a few concrete examples of its applications.

Motivating (simple) example: calculating the pub bill

Let’s set the context. You want to design a computer program that will calculate your pub bill based on the number of beers you ordered. Let’s assume each pint costs 5£ (yes, life in London in expensive).

Traditional programming

In traditional programming, you would tell the computer that:

- a pint costs 5£

- the formula to calculate the the total cost is <5 * number of pints>

And then you would input the number of pints you drunk and let the computer do the math.

For instance if you drunk 3 pints, the computer will calculate 5*3 and return 15. Easy :)

Machine learning

In machine learning, the process is a bit different.

You start with the learning phase:

- you provide the following information to the computer:

| Number of pints | Price in £ |

|---|---|

| 3 | 15 |

| 5 | 25 |

| 10 | 50 |

- you tell the computer: go figure out the best formula to predict my total bill (using a learning method you will suggest, many exists but this is not the topic of this post)

Then you move to the prediction phase:

- you input how many pints you drunk

- you ask the machine to calculate the bill based on the magic formula it came up with.

If the data scientist suggested the right learning method, the program will have figured that a pint costs 5£ and also return 15£ total bill for 3 pints.

As you can see the main difference is that in the first case, someone has already figured out the relationship between the number of pints and the total price, whereas in machine learning, you ask the computer to find out by itself.

How does the training phase work?

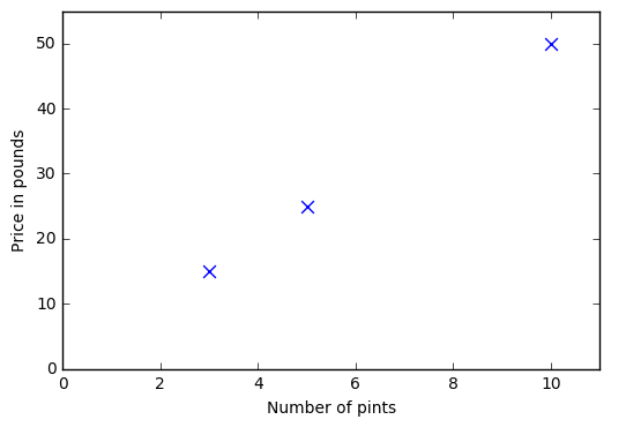

To understand a bit better how the learning phase works, we have to represent ourselves the information available to the computer. We displayed it earlier under the form of a table, but visually it looks like this:

Each blue cross represents a row in the table from previous section. On the horizontal axis, we see the number of pints, on the vertical axis the associated price. So the first cross at the bottom left tells us that 3 pints cost 15 £.

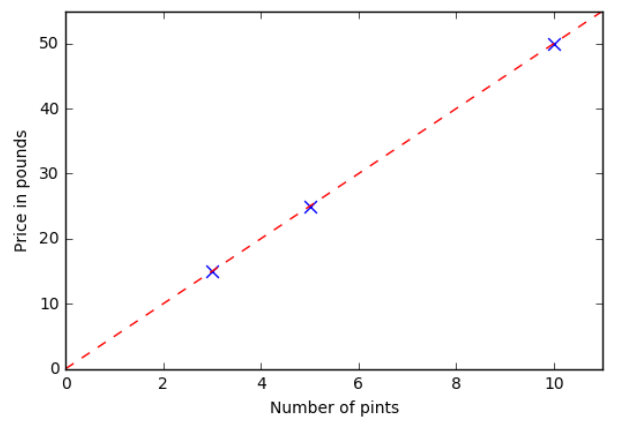

The job of the data scientist is to tell the computer what learning method to use, based on his knowledge of the problem he is trying to solve.

In this case, the computer scientist will ask the compute to fit a straight line through all the points. As a result we get something linke this:

Now, to calculate the cost of a new number of pints that we didn’t have in our training set, the computer will do something equivalent to putting a new cross on the line at the right horizontal position corresponding to this new number of pints, and read the associated price on the vertical axis.

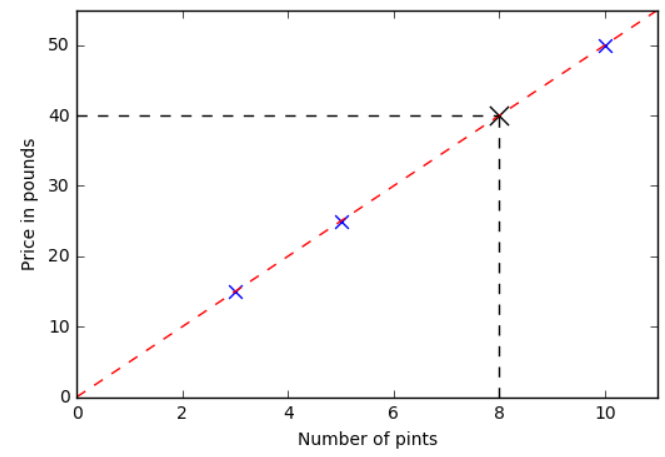

For instance, for 8 pints:

It’s easy to read that the price is 40£.

Of course there are many different learning algorithm, and fitting a straight line is the most simple of them, but in essence this is how it works.

Some real life examples

So far I am sure that the example makes sense but doesn’t look too impressive. Sure, you don’t need a computer to guess that a pint costs 5£ if two pints cost 10£!

Let’s define a bit of vocabulary:

In machine learning the number of pints is also called predictor and the price outcome.

The magic in the background is called model or algorithm.

In real life problems, you may use tens, hundreds and even sometimes thousands of predictors to build your model. What may seem super easy for a human with one outcome and one predictor becomes already almost impossible with 2. With 3 predictors or more, you move into multi-dimensional spaces that the mind can’t represent, and you anyway deal with too many information to make sense out of it.

Yet computer are powerful enough to figure out!

Netflix recommendation system

Whenever you watch a movie on netflix, you are encouraged to rate it. You may think of you doing a courtesy to other viewers to let them know if the movie is worth investing 2 hours of their time and a few pounds (or dollars, or euros…)

Well, you are kind of right. But mostly you are doing a courtesy to Netflix whose machine learns to understand your tastes and associate them with that of hundreds of thousands of other customers. By comparing set of movies that were liked by the same people, netflix creates categories of viewers. Once a new movie is released, if a few people from a category rate it well, it is highly probably that other people from the category will like it too, so Netflix can recommend it to them.

And here you go… more business for netflix!

This is a famous example in data science as Netflix started a contest in 2009, with a 1 million $ price for the team who could come up with the best recommendation algorithm possible. As it turned out the team who won the price had develop such a complex algorithm that it was too slow to process for the needs of the company, so it was effectively never used.

Predicting house prices

If you are a real estate agent and want to price appropriately a new house that you have to sell, how do you do?

One option is to collect data from many houses, including price along with information such as location, size, number of rooms, age, type of material used for construction, area crime rate etc.

Then you let the machine do its magic and come up with a nice prediction algorithm that you can feed with new data from your new house, and you get its price as an output.

Patterns recognition

In order to process more efficiently paper mail, post offices from many countries over the world have long asked their customers to write zip codes in well defined areas printed on envelopes.

The idea is obviously to get the bulk of the mail sorting done by machines. How does it work? If you feed a computer with many, many examples of handwritten digits or letters and tell them each time what each sign corresponds to, it will eventually learn to recognise digits or letters written by people whose handwritting it has never seen before.

Limitations of Machine Learning

It’s important to keep in mind some limitations of machine learning.

Quality of the model

Your prediction is always as good as the model you define.

In many cases, we don’t know the exact nature of the phenomenon we want to modelize. Therefore choosing the right model is much harder than fitting a staight line from our beer example above. If you picked the wrong training algorithm, or you don’t have enough data to train properly, or if you use too many variables, your model can be completely wrong and make useless predictions.

Therefore, a lot of care must be taken in the design of the model, and usually knowledge of the data you are dealing with is required to achieve the highest quality. This is what makes data science so interesting. It requires a mix of scientific, technical and business skills to suceed

Interpretability of the model

There is a growing concern that human are not necessarily able to interpret the model built by the computer. In fact there has recently been several articles in newspaper reporting fear of the “algorithm”, as more and more decisions impacting people’s life are performed by computers based on machine learning models. The latest article I read talked about how french students are assigned to a university or another based on criteria that no one seems to understand anymore.

In some cases, models are easy to interpret (think of our example of the pints and price). But in many cases, models are so complex and use so many predictors that understanding the logic behind it is extremly difficult, if not impossible.

My bet is that in the future governments will issue policies forcing companies or administration to provide the logic behing their machine learning algorithm. Data scientists should better get ready for it now!

Further readings

Artical from Le Monde 2016, September 19th (in french)